Umwelt: Talk to the flowers

Mediums: Metal, Cellophane, Paper Daisies, TPC heating elements, wire, thread, dirt, moisture, heat, rice-paper

Dimensions approximate in mm (W,D,H): 600x600x2000

Exhibition: FAM+ 25

Exhibition date: 29th of October- 5th of November 2025 at the Cullity Gallery UWA

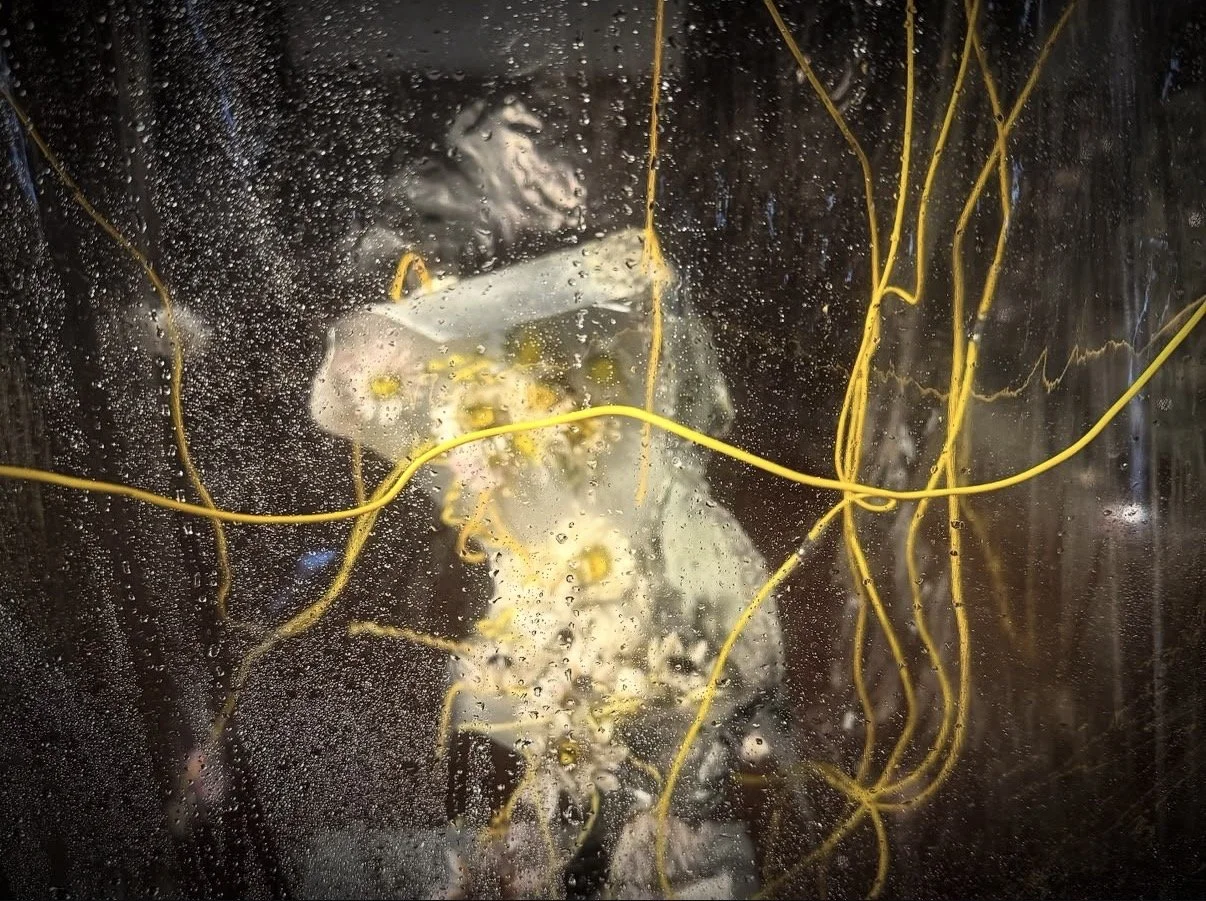

Metal terrariums wrapped in semi-permeable material, housing statues of paper daisies and

heating elements. Wires from the heating elements sprawl across the ceiling whilst moisture

and heat control the opening and closing of the flowers.

“Umwelt: Talk to the flowers” is an installation comprising three living systems that animate paper daisies through controlled heat and moisture. Each metal chamber, sealed with semi-permeable cellophane, houses a contorted metallic statue embedded with paper daisies. Wires from the heating elements pierce the chamber walls, webbing across the space like a connective network. Cycles of condensation and heating cause the paper petals to slowly open and close, giving the sculptures a breathing rhythm, echoing a soundscape of organic tones and reinforcing the installation’s sense of vitality.

Blurring floriography and interspecies communication, the installation invites audiences to speak their troubles to the flowers. The humidity of their words functions as a communicative medium within the flower’s Umwelt, prompting a poetic response through influencing the flower’s movement. This ritualistic exchange, renders the flowers as intelligent responsive bodies, shaped by proximity, voice, and human presence. “Umwelt: Talk to the flowers” speculates on a world in which flora is a therapeutic language which builds pathways toward kinship, empathy, and ecological reconciliation.

Research:

By knowing a species Umwelt, we can find new ways to directly communicate with them. Umwelt is the perceptual world of a species. It’s a non-communicating perceptual world, but we can use it as a common ground to communicate through. To bridge a communication between species, one species must be able to tap into the Umwelt of another species and share information through it using the same medium as its Umwelt (1). Our perceptual world is subjective and builds our model of reality based on how we receive the environment around us. How we construct our world is based on a feedback loop. The sensory experiences from our Umwelt are inputs of information from our environment. Our past experiences and feelings then check this information and decide if we agree with it or not, then it gets stored in our memory and is learnt. Our model of reality defines our belief system, personality, and identity. Therefore, our Umwelt establishes our processing patterns which establish our version of reality (2). For a human, our sensors include auditory, visual, and touch. But for other species, it varies. In Tomas Saraceno’s case, a spider’s model of reality is based on vibrational communication as well as sight. In the case of a canine, it’s their sense of smell and night vision (3).

The entire process was quite meditative and ritualistic, as I entangled humans with a plant by harnessing its Umwelt. Not only does this pass the boundary of becoming-molecular but it also creates a network of actants, through the audience changing the humidity of the environment which effects the way paper daisies open and close; although theoretically, the moisture level from each word spoken into the chamber would eventually diffuse, and the moisture levels in the chamber would equalise. This would cause the distinct moisture patterns that made each message unique to fade, effectively erasing the message. My artwork disregards this aspect to enhance the world-building and its speculative function. It instead debates that our relationship with the daisies is an affective one, the daisy responds to the messages through molecularly changing it inside the bracts of the flower, then releasing it. We cannot hear this response but because moisture can pass in an out of the cellophane, it slightly effects the humidity of our environment, outside the chamber through a process called diffusion.

Floriography is the study of the symbolic meanings and semiotics of flowers. It links meanings to the colours and types of flowers (4). Historically, they are coded messages disguised in bouquets (5). In floriography, flowers are merely the messenger, agency isn’t recognised and kinship is not formed. In the example of paper daisies, their floriographical meaning is linked to healing, everlasting happiness, resilience and beauty. My artwork uses the daisy’s symbolic healing qualities to provide a platform where the audience can participate in a performance art of catharsis. Just like, writing down your troubles on paper, scrunching it up, and burning it to let go of what ails you, they can now talk to the flowers, and they will let go of your troubles for you.

Interspecies communication is a critical theory which promotes a relationship between two species where we are devoid of a common language (6). Research in this field aims to find ways of establishing communication with them through a non-anthropocentric way, forming new ways of understanding non-humans and creating two-way interactions. It transcends the use of symbolic language through exploring cognitive science (7).

Interspecies art is a post-human art movement which is interwoven with ecofeminism. It promotes how dissonant relationships with the ‘other’ can still be empathetic ones. Empathetic encounters materialise as care, compassion, and the recognition of agency without any individual benefit or expecting anything in return. Interspecies art aims to teach empathy and break anthropocentric hierarchies between our co-habitants through concepts which do not include human and non-human suffering. It speculates on worlds that are non-utilitarian or hierarchical and allows us to imagine non-human worlds. Successful interspecies art prioritises the importance of connection rather than individuality through using a network of actants (8). This means that humans and non-humans are equal partners which affect, influence or shape each-other within a shared environment to create an assemblage (9).Actants based on care and speculation create kinship and form a reconciliation with the world and our animality (10).

Process:

I cut mild steel rods to size and created prism-like shapes. They were welded together to create the skeleton structure of the chambers. Cellophane was wrapped, hot-glued and stitched onto the skeleton to enclose it. I cut out thin sheets of metal using a guillotine and an angle grinder to create the trays, banging the sides of the metal against a table edge to bend the sides.

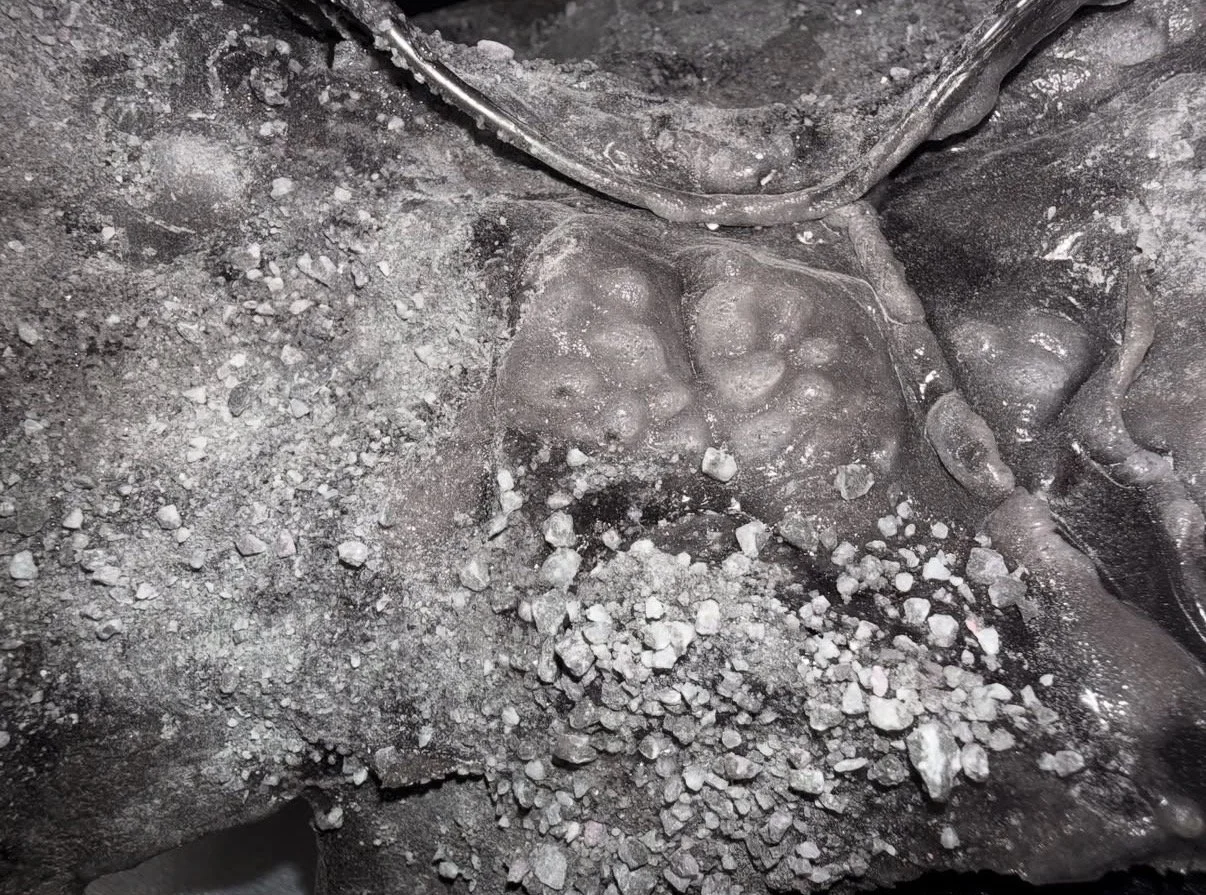

The plinths were made using wood and rice-paper, which echoed throughout the metal statues ontop of them. The rice-paper was dyed and then burnt to create the bubble effect. Crushed up pebbles were glued onto the rice-paper to make them look more like organic stones. I put varnish on the plinths so the moisture wouldn’t rot them.

The heating elements had 3m long wires, and were stuck onto the metal using heat resistant tape. They get up to approximately 140 degrees in a very small circumference, heating up the metal statues enough to dry out the flowers. This is regulated by a wall-timer. So I know when the heating elements are activated or not, I used a temperature gun and I made it so they turn of and on every 15 minutes, Indicated by the breathing in the soundscape.

Footnotes:

Falguni Desai, Floriography in Tagore’s Poetry. Muse India International online e journal. No.33. (2022) https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4219991

2. J. R. Mcgrew & Anne M. Hanchek, The Language of Flowers. Hortscience. Vol 28, No. 5 (1993): 452–4452, https://doi.org/10.21273/hortsci.28.5.452c

3. Tomás Saraceno, Ally Bisshop, Adrian Krell, Roland Mühlethaler, Arachnid Orchestras: Artistic Research in Vibrational Interspecies Communication. Biotremology: Studying Vibrational Behavior. (2019): 485-509.

10.1007/978-3-030-22293-2_24

4. S. Alenka Brown-VanHoozer, Models Of Reality. (199)

5. Paul E. Miller & Christopher J. Murphy, Vision in Dogs. Vol 1, No. 49 (1996): 60 https://www.infona.pl/resource/bwmeta1.element.elsevier-5fac304e-ddc2-32ab-8c71-3a8e5e5901c5/tab/summary

Andrés Richarte, Animales no humanos: un acercamiento al otro desde la práctica artística (2022)

10.4995/ANIAV2022.2022.1549

6. Bill Giannakopoulos, Persistence Theory and Interspecies Communication: Toward a Thermodynamic Grammar of Shared Meaning. OSFPreprint. (2025)

7. Carmen Gutiérrez Jordano, Carmen Andreu Lara, “ARTE DE CONTACTO INTERESPECIES: LAS PRÁCTICAS ARTÍSTICAS CONTEMPORÁNEAS DE CUIDADO HACIA LOS ANIMALES NO HUMANOS” AusArt: Ecologia Y Arte. (2024)

Kristin A. Blanton, Actor-Network Theory and Animal Therapy: Uncovering

the Relational Ecology of the Exceptional Student

Classroom. Jack N. Averitt, College of graduate studies. (2019)

9. Carmen Gutiérrez Jordano, Carmen Andreu Lara, “ARTE DE CONTACTO INTERESPECIES: LAS PRÁCTICAS ARTÍSTICAS CONTEMPORÁNEAS DE CUIDADO HACIA LOS ANIMALES NO HUMANOS” AusArt: Ecologia Y Arte. (2024)

Video Of Flowers Closing